What is the meaning of OM?

As part of the philosophy component of the yoga teacher training I undertook at Yoga West, I wrote an essay on the meaning of OM. I have edited it a little for clarity and format, but otherwise reproducing here on the blog! You can also read my essay on: “Why practice Yoga?” here, which I also wrote as part of the training.

In my research into the meaning of OM, I quickly discovered that although chanting OM is common at the start of most yoga classes, there arevery few resources available online that are comprehensive and cover the many ways we can interpret and understand OM. This essay consolidates my research and I hope you will find it useful in understanding the meaning of OM. Happy reading….!

As the practice of yoga asana (postural yoga practice) spreads globally, access to information increases along with the movement of populations, the symbol for OM in Devanagari script, is now highly recognisable around the world. But do you know what it means?

Many practitioners of yoga asana in the UK would recognise this symbol from its use on merchandise, printed on bags and yoga mats, and it is often referred to as the “Namaste” symbol. A quick google search for Namaste and the image of the devangari script OM will immediately pop up.

OM has historically been used as a greeting in India along with Namaste, and, like Namaste, it is often spoken or chanted in yoga asana classes by students unaware its origin, its meaning or significance within not only Hinduism but multiple world religions and belief systems, and in the practice of yoga.

Read on to find out more about the origin, meaning and interpretation of OM in the sacred scriptures, as well as its historical and modern usage.

Origin of OM

The earliest record of OM is in the Upaniṣads, ancient Sanskrit texts which form part of the foundational teachings of Hinduism.

The Upaniṣads are dated as far back as 700BC and were preceded by the Vedas. Several Upaniṣads mention the OM, and the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad is devoted directly to this subject. The OM can also be found in the Bhagavad Gita, written during the same era as the Upaniṣads as part of the epic Mahābārata text, and the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali which consolidated the teachings of yoga into 196 sutras, or short verses, toward the end of the Upaniṣad period.

The Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad is a short, direct text consisting of only 12 verses, explaining exclusively the OM. This Upaniṣad is considered by many to form the core of the teachings of the Upaniṣads, and it is said that through its study, it is possible to learn teachings of ALL the Upaniṣads.

For example, Swami Krishnananda of the Divine Life society in Rishikesh, India has said of this Upaniṣad:

“If you are able to understand the true meaning of this single Upanishad, there may not be a necessity to study any other Upanishad, not even the Chhāndogya or the Brihadāranyaka, because the theme of the Māndūkya Upanishad is a direct approach to the depths of human nature.“

Swami Krishnananda

The OM written is Devanagari script may be the symbol you recognise, however there are many representations of OM in different scripts around the world. Take a look at the OM symbols in Tamil and Malayalam script.

Understanding OM

The first verse of the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad identifies the OM as a symbol of all existence, and all-compassing relative to time:

“What is called past, present and future is all just OM. Whatever else there is, beyond the three times, that too is all just OM.”

Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad, Verse 1, Translation by Roebuck

The following verse identifies this all as being Brahman, which also encompasses the self, the Ᾱtman:

“All this is brahman. The self is brahman.”

Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad, Verse 1, Translation by Roebuck

It is interesting to note that the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad does not distinguish the personal Isvāra, or a personal deity, but is referring to Brahman as the impersonal consciousness that encompasses all.

The Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad also does not explicitly separate the material world, prakriti, as in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, but this must be assumed to be a part of Brahman as its definition is all-encompassing in the absolute.

However, in the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali states OM to refer to Isvara, a personal deity. In Sutra 1.27 Patanjali states:

“The name designating him is the mystical syllable OM.”

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, 1.27, Translation by Bryant

The use of the personal pronoun “him” refers to the supreme personal being, Isvara, whose nature is discussed in the preceding Sutras. Depending on the source text, the OM can therefore be understood to represent a supreme personal being, Isvara, or supreme impersonal consciousness, Brahman. However, both are all-encompassing, and share the same designation: OM.

Sri Swami Satchidananda has an interesting take in his commentary on this sutra:

“Patanjali wants a name that can give an unlimited idea and vibration and which can include all vibrations, all sounds and syllables, because God is like that – infinite”

Commentary to the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali by Sri Swami Satchidananda

The OM then is a means to understand Brahman or Isvara, as it is seen to be as all-encompassing as that which it represents.

The four quarters of the Atman and OM

Verse 2 of the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad goes on to state that the Self, the Atman, (which we have already established is of Brahman) has four parts, padas, translated as either quarters or feet.

The Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad first provides detail on those 4 parts in verses 3-7, before going on to draw comparison between each part and the syllables of OM in verses 8-12. The 4 quarters of the Self, the Atman, outlined in verses 3-7 are as follows:

| Quarter | Verse | Name | State | Description of consciousness |

| 1 | 3 | Vaiśvānara | Waking Consciousness | External or outward-facing |

| 2 | 4 | Taijasa | Dream state | Internal or inward-facing |

| 3 | 5 | Prajna | Deep Sleep | Mass of consciousness |

| 4 | 7 | Turiya | Unrealised | Unknowable |

The first quarter, Vaiśvānara, waking consciousness, is described as experiencing gross objects, meaning the external reality as experienced through the senses of sound, touch etc.

According to commentary by Yogananda, gross objects can be subdivided into two: the microcosmic and the macrocosmic. The microcosmic is the subjective experience, and the macrocosmic the objective experience, therefore:

“A parallelism runs through the subjective and the objective. The macrocosm is superimposed upon Brahman, and the microcosm upon Atman, through avidya. Both are illusory appearances. On account of the non-difference between the subjective and the objective, the limbs of Vaisvanara are described in terms of the objective universe. The purpose is to show the illusory nature of the entire phenomenal world and establish the non-duality of Atman and Brahman.”

Paramahansa Yogananda

The description of the Atman through means of the 4 quarters are based on human experience of the objective universe, and in doing so, establishes the unity of Atman and Brahman as OM.

Verse 8 then goes on to divide the OM into components parts, “the feet are the elements and the elements are the feet: ‘a’, ‘u’, ‘m’”. The subsequent 3 verses draw parallels between each state of the Self, Atman, and the component parts of OM as AUM. Verse 12 then adds a fourth component, Turiya. The four component parts of OM are therefore:

A + U + M + Turiya

These four parts, or quarters, correspond to the aforementioned quarters of Atman as follows:

| OṂ | Quarter | Verse | Name | State | Description |

| A | 1 | 3 | Vaiśvānara | Waking Consciousness | External or outward-facing |

| U | 2 | 4 | Taijasa | Dream state | Internal or inward-facing |

| M | 3 | 5 | Prajna | Deep Sleep | Mass of consciousness |

| Turiya | 4 | 7 | Atman | Unrealised | Unknown |

Turiya, sometimes written as Turya, is represented by the silence which follows the OM. As pure consciousness, it is also pure potentiality, and as such the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad describes Atman as “unthinkable, unnameable”.

The Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad goes on to state that the Atman is “without duality”, advaita, and thus references maya, the illusion of duality, which prevents Atman from realising its true form as Brahman.

Atman therefore, like Turiya, or pure potentiality, cannot be known or described in words, only experienced. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali then set out a pathway through yoga to experience Samadhi, meditative absorption, and ultimately moksha, liberation, the ultimate removal of the veil of ignorance and the realisation of Atman as Brahman.

The meaning of the written symbol of OM

Although often printed in sacred texts, the written symbol of OM is not addressed in the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad, and the OM can be written in a variety of ways depending on the script used or the cultural and religious history in which the OM is found.

However, its representation through the Devanagari script has become synonymous with OM, as well as a symbol of the Hindu religion (a search on Google for “Hinduism” shows the OM as its motif, for example).

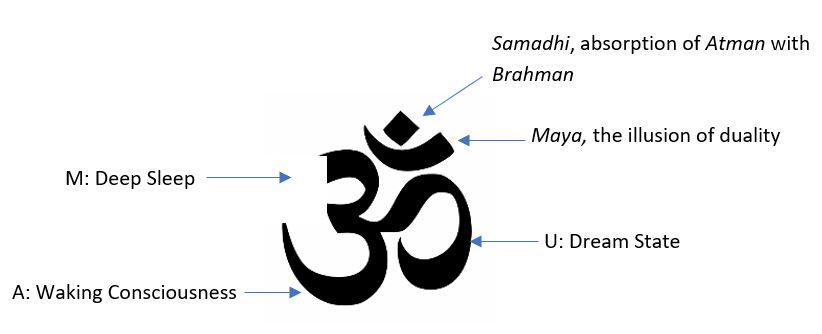

Each element of the written symbol can be seen to represent an aspect of OM, or more specifically AUM.

The bottom left curve is seen to represent the waking consciousness, A

The the right-hand curve represents the dream state, U

The upper left curve represents the deep sleep state, M

The dot at the top represents the fourth state in union with Brahman, in other words Samadhi.

The line which separates samadhi from the other three states represents the illusion of duality, maya. The diagram below illustrates these sections:

This interpretation of the written OM in Devanagari script is not mentioned in the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad, but it is widely used as a metaphor within Hindu teachings in explaining the OM.

Trios and quarters

Trios and quarters are both relevant and significant to the understanding of OM. The 3 letters AUM can be seen to correspond to the 3 manifestations of the divine, Trimurti, as follows:

| A | Brahma | Creator |

| U | Vishnu | Preserver |

| M | Shiva | Destroyer |

The OM is also referenced in the Maitri Upaniṣad, where it is described as a series of trios in book VI, verse 5:

“Feminine, masculine and neuter are its gender-body. Fire, air and the sun are its light-body. Brahma, Rudra and Visnu are its overlord-body. The Garhapatya, Daksinagni and Ahavaniya are its mouth body. Rc yajus and saman are its knowledge-body. BHUh, DHUVAh and SVAh are its world-body. Past, present and future are its time-body. Breath, fire and sun are its heat-body. Food water and moon are its growing-body. Intelligence, mind and sense of ‘I’ are its consciousness-body. Breath, lower breath and diffused breath are its breath-body. So by saying OṂ these bodies come to be praised, worshipped and achieved”

Maitri Upanishad

The three sounds have also been interpreted to represent the three gunas, which form material existence or nature, prakriti. However, by including Turiya, there are in fact four components or quarters to the OM (and therefore the Atman and Brahman).

There is a parallel to Brahma, the creator, or personal manifestation of Brahman, who is said to have four heads, expressed in the four Vedas, the four ages (yugas), the four social classes (varnas), as well as many other four-part representations in Hindu theology.

Similarly, to return to the first verse of the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad, there are four elements: 1) Past 2) Present 3) Future 4) Anything else.

This Upaniṣad divides the self, Atman, into four quarters, corresponding to the four components of OM. Similarly, the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali consist of four padas, translated often as feet, or books or chapters. Trios and quarters are therefore significant subdivisions within Hindu and yoga theology and its foundational sacred texts.

OM as a means to Samadhi

Although the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad gives a clear and direct overview of OM, in terms of meaning, understanding, and scope, it does not give any direction to the reader on why or how it should be chanted, or, for that matter, whether it should be chanted or spoken aloud at all.

However, the Bhagavad Gita references the chanting of OM several times throughout the text, and in the 8th discourse Krishna, the manifestation of Vishnu, gives direction to the warrior Arjuna as follows:

“13

Bhagavad Gita, 8th Discourse, Verse 13

when one has said ‘Om’;

the Brahman of one syllable,

meditating on me,

one goes forth,

abandons the body,

and then travels

the highest way.”

The direction is therefore that OM should be said prior to meditation on Krishna, as the personal manifestation of Brahman.

Yet, the repeated chanting, japa, of OM has been a central practice of Yogis since the late Vedic period. Patanjali is much clearer and more direct on this point in Sutra 1.28, stating:

“Its repetition and contemplation of its meaning [should be performed].“

Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, Translation by Edwin Bryant

Sutra 1.29 goes on to state that doing so results in freedom from all disturbances, and is a means of samadhi, absorption ‘with seed’. The latter refers to an object of focus in meditation, which in this case would be the repetition of OM, as a means to reach the state preceding ‘seedless’ samadhi.

The following Sutras offer a selection of options for this seed, or object of focus, before Sutra 1.39 states:

“Or [steadiness of the mind is attained] from meditation upon anything of one’s inclination.”

Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, Translation by Edwin Bryant

As verse 2 of the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad states, Brahman is all-encompassing and it thus follows that any object can be a point of focus, or seed, for meditation. This is explained clearly by Swami Krishnananda in his commentary on the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad:

“We may be sitting in our rooms, and the first things that attract our attention may be the objects spread out in the rooms… And, the moment the object that is conceived by the mind is identified with the Cosmic Body, the object ceases to agitate the mind any more… When an object becomes a part of our own body, it no more annoys us because it is not an object at all. It is a subject.”

Swami Krishnananda

It is for this reason then, that it is said that self can be realised through the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad alone. As OM is understood to be all-encompassing, and any object can be a means through which to reach samadhi with seed, the final stage preceding (seedless) samadhi.

However, unlike other named objects, OM is understood to have an intrinsic connection to that which it evokes. In other words, whilst most objects are named for the purposes of convenience, to take the example used by Edwin Bryant in his commentary on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, a cow could just as easily be called abracadabra; the word cow does not have a binding relationship with that which it refers to, it is a convention.

Vācaspati Miśra states that OM is “eternally invested by Isvara with his power” and therefore that “not being subject to Time, Isvara is not subject to cyclical creation and therefore can invest his potency eternally into the sacred syllable OM”

Chanting OM is therefore a means to evoke and experience that which OM represents, rather than simply being a psychological means to conceptualise a supreme consciousness. (See Bryant commentary on the Sutras, p.107)

The meaning of OM in yoga asana practice

With an understanding then of OM, why is it commonly chanted at the start and end of yoga asana practice? Many studios will typically start and finish a class with repeated chants of OM, with variations on the chants used depending on the style.

In Hindu tradition, OM is used as the opening and closing to prayers and chants. The prayers stated at the start of each Upaniṣad commence with OM, so it is possible that over time, the longer chants have been removed from practice as yoga asana has become more secular in nature to appeal to those of different faiths.

Yoganand Michael Carroll of the Kripalu School of Yoga in the US is quoted in the Huffington Post saying: “We chant it because yogis have for thousands of years. And when we chant it, we’re connecting with those yogis in a ritual way, and drawing upon the support of the practices they’ve been doing for a long, long time.”

There is therefore a sense of ritualization of practice combined with a sense of drawing together as a community. It can serve as an intention at the start of yoga asana practice to ensure the practice is devotional in nature, setting the tone for the practice as being spiritual rather than simply physical exercise for the body.

The physical act of creating the OM sound with the eyes closed nevertheless can have benefit in stilling the mind, by withdrawing the senses (sight) and bringing a point of focus of the mind. Creating the sound also requires breath, thus the mind is brought to focus on the flow of breath.

The meaning of OM

The meaning of OM is complex, multifaceted, and yet simple: it is all.

The meaning of OM has not evolved or changed from its original explanation in the Mānḍūkya Upaniṣad; however, further clarity, explanation and direction on usage through chanting, japa, have been attributed to it over time.

In particular, as Patanjali systematised the teachings of yoga from a variety of sources, he codified the tradition of japa as part of the pathways of yoga.

In modern yoga studios, OM is part of a tradition that is used as a means to connect with the community, creating a shared space and experience. Those in the studio may be at different stages along their path of yoga or may even be taking their first tentative and wobbly steps into unknown waters. Chanting OM is therefore a means to unite those at all stages of (self)-study, svadyaya, and offers practitioners a stand-alone pathway to samadhi.

For many practitioners of yoga, chanting OM is no longer a practice in and of itself but part of a series of interlinked practices, along with yoga asana, pranayama and meditation, (amongst other practices) seen as a means to connect to a sense of spirituality, but this may be through connection to fellow practitioners in the studio or yoga community, or to bring about a sense of going inward toward a greater awareness of self. In this sense can therefore nevertheless be seen to still serve the same purpose as it has for yogis for many centuries.